eCommerce brands have a variety of techniques at their disposal for understanding their customers and optimizing their KPIs: most of these techniques have been borrowed from modern product management practices and can be directly applied to eCommerce–A/B testing is one of these.

A/B testing (sometimes referred to as “split testing”) is a technique that uses statistical algorithms to determine which variation of a given behavior is most likely to optimize for a predetermined quantitative outcome. By using live traffic to analyze user behavior, A/B testing can provide an objective, data-driven answer to nebulous questions, such as whether offering free shipping to your customers will significantly affect add-to-cart rates.

With that said, A/B testing is one of many techniques brands can employ and arguably one of the most complicated to execute correctly. Unfortunately, we often see brand founders and executives jump into A/B testing without clearly understanding the required skillset or effort, only to arrive at disappointing conclusions and abandon the practice altogether.

We firmly believe that A/B testing has its place. Still, we also have strong opinions about when it should and shouldn’t be employed and the requirements for running a successful A/B testing operation. In this guide, we will break down some of the complexity behind A/B testing, help you understand whether it’s a good option for your brand, and offer practical tips and considerations for rolling it out.

A Primer on How A/B Testing Works

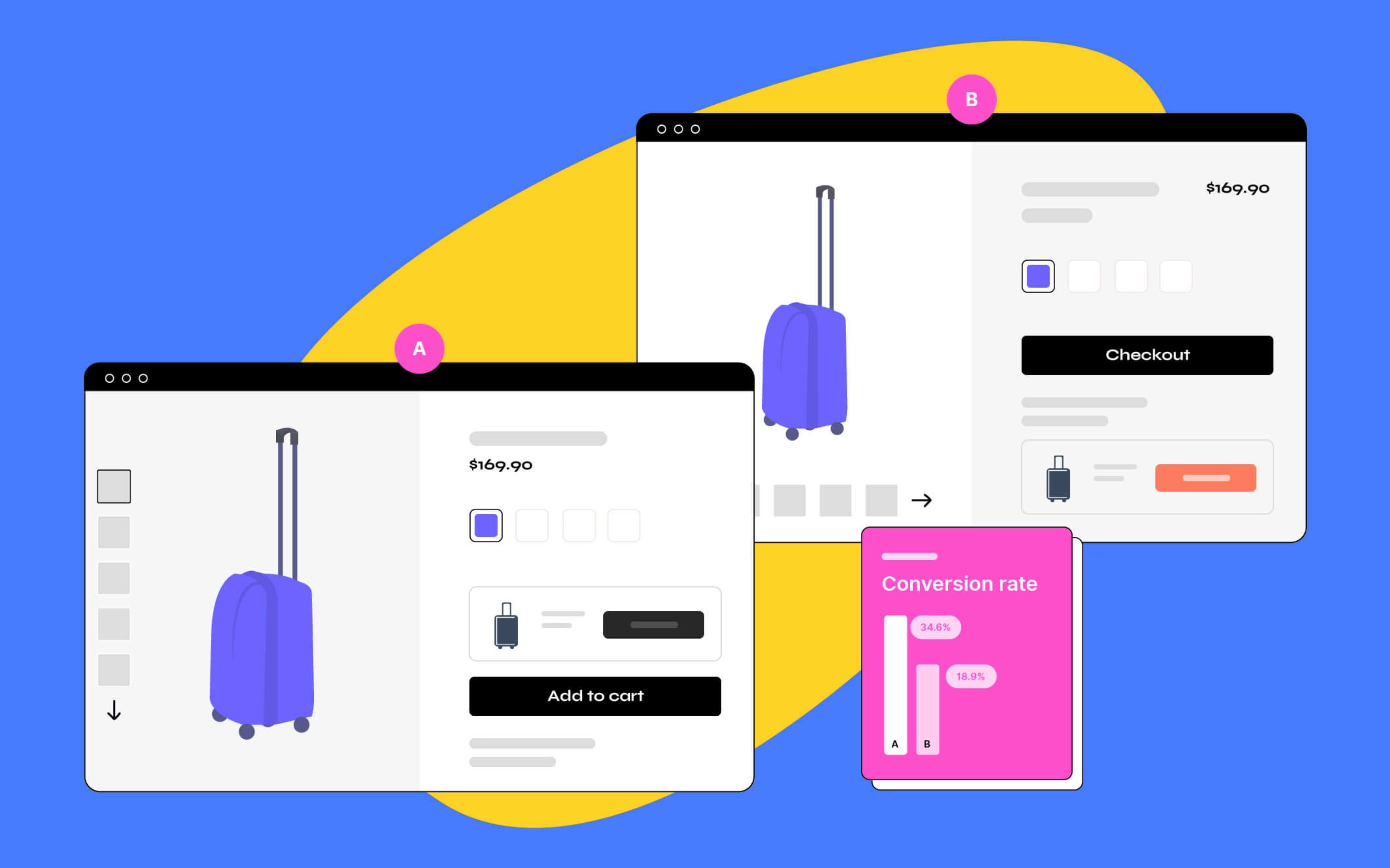

At its core, A/B testing is a simple concept: we design two variations of the same web page (version A and version B), distribute our traffic evenly among the two variations, then see which one reported the best performance.

Going back to the “free shipping” example, an online store could show a free shipping banner to half their customers (this is the experiment group) and use the original page for the other half (this is the control group). At the end of the test, whatever version got the highest conversion rate would be considered a winner (with some statistical caveats).

This is the simplest possible type of A/B testing, but there are a few alternatives:

- In A/B/n testing, more than two variations are tested (e.g., no free shipping indication vs. a free shipping banner vs. a free shipping popup).

- In multivariate testing, each variation alters multiple elements on the page (e.g., a free shipping banner and a popup, just the banner, just the popup, no free shipping indication).

- In bandit testing, more and more traffic is automatically directed to the winning variation (e.g., if the free shipping banner converts more than the original page, we automatically start showing it more and more often).

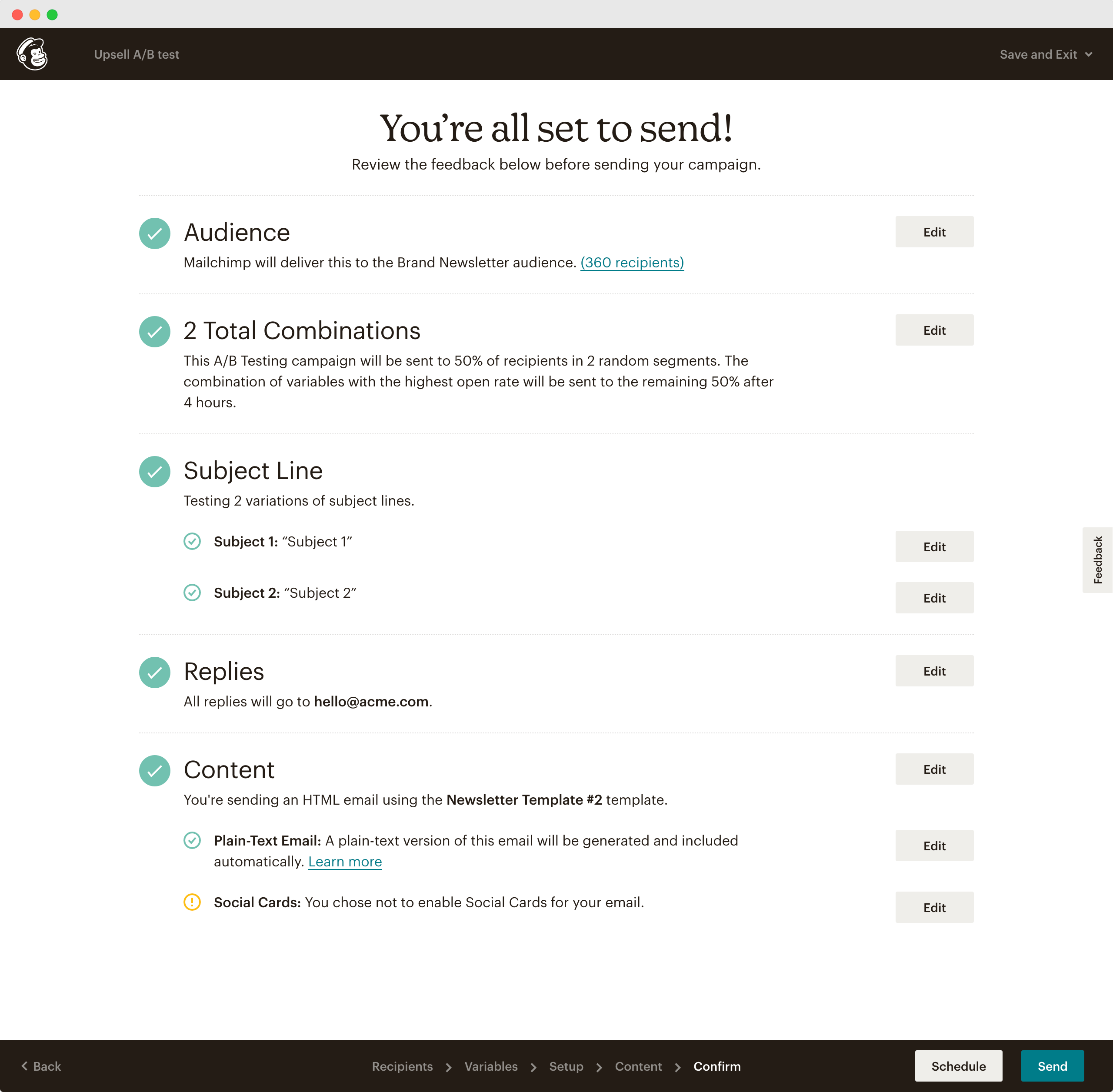

It’s important to note that while this article talks specifically about A/B testing web pages, the technique can be applied—at least to an extent—to email marketing, social media, and other types of digital properties. Furthermore, eCommerce platforms, marketplaces, and marketing tools often provide native A/B testing capabilities:

- Amazon allows its merchants to A/B test content such as product images

- Hubspot allows testing landing page templates and email campaigns.

- Google Ads allows testing different ads to optimize clickthrough rates.

These concepts are deceptively simple, which is why so many A/B testing platforms promise exceptional ROI and quick results. In reality, A/B testing comes with many pitfalls and “gotchas” that practitioners should understand thoroughly. Running an effective A/B testing operation on an eCommerce website requires significant preparation, effort, and discipline.

What an Effective A/B Testing Process Looks Like

Let’s take a peek into what a successful, effective A/B testing operation looks like in detail.

1. Picking a Problem Space

There are many resources online advertising “the best 99 A/B testing ideas,” and it might be tempting for inexperienced executives to jump in and start testing. Unfortunately, these blanket experiments are unlikely to move the needle–in some cases, they might even be detrimental to a brand’s KPIs. Furthermore, they completely ignore the true purpose of A/B testing, which is not conversion rate optimization but refining our understanding of our market, business, and customers.

For this reason, before diving head-first into changing the color of our CTA buttons, we must understand the problem space we want to explore. This can be a very narrow product opportunity, such as whether a new version of the search functionality will lead to better recommendations, or a broader area of the business that we want to understand better, such as how we can improve our conversion rates during the checkout process.

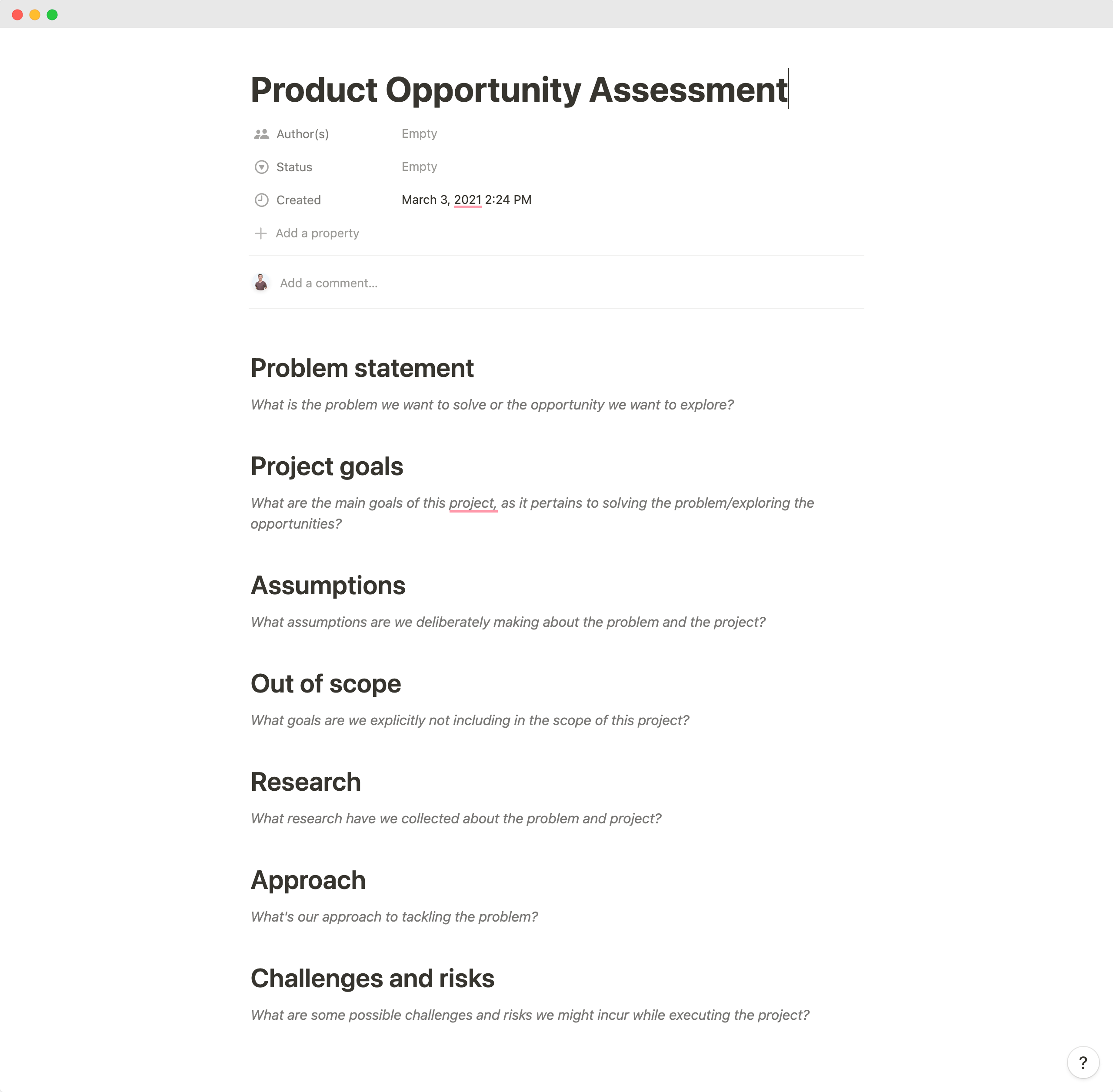

Whatever the case, we need to articulate precisely what questions we want to answer and why we think an A/B test is the correct methodology to answer them. This is most often done through a Product Opportunity Assessment (POA), a document that explains what problem we’re solving and for whom, analyzes the market and the problem space, any business- and customer-facing implications of solving the problem, and provides a final recommendation (go/no-go) based on the information we have collected.

A/B testing, when employed correctly, is an invaluable tool that allows eCommerce product managers to quantitatively confirm or disprove existing hypotheses related to a particular opportunity. Still, it’s not a replacement for picking and refining an opportunity in the first place. Unfortunately, brand executives and marketers sometimes fall into the trap of running mindlessly through a list of standard A/B tests, leading to short-term, black-box optimizations at best and a waste of resources.

2. Designing the Test

Once the opportunity is well understood and prioritized, it’s time to design the A/B test. The first step is formulating a hypothesis that we want to confirm or disproven, which usually looks like this:

We think that, by [experiment], we can increase [metric] by an [absolute/relative] [Minimum Detectable Effect]%.

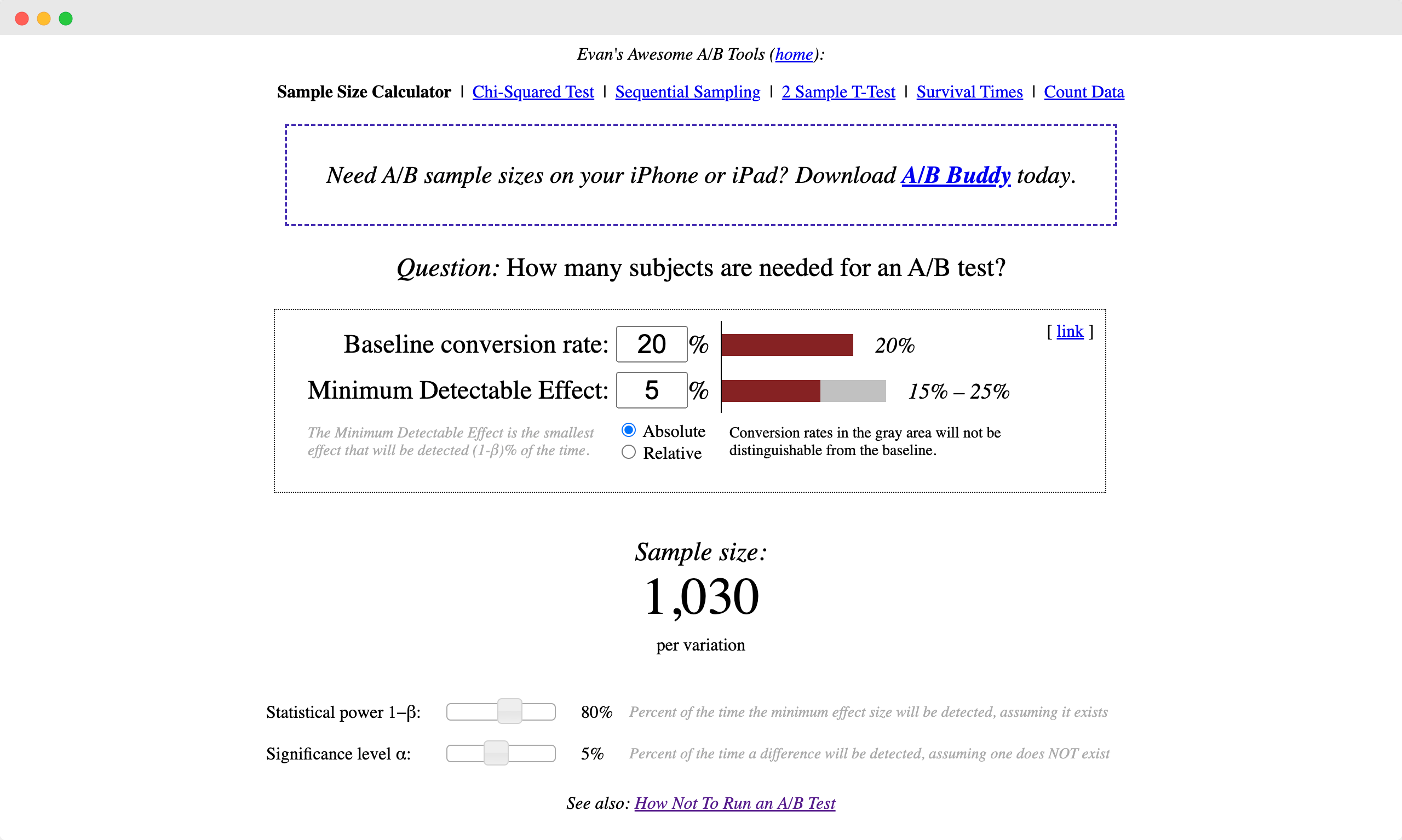

Stating the hypothesis is the first step, but we will need a few more elements before launching our experiment. In particular, we need to establish the following:

- Our current conversion rate. If we don’t have it, this is a good time to stop and put the proper instrumentation in place.

- The desired statistical power. This indicates how likely we are to detect a difference between the control and the experiment, assuming it exists. Higher values give us more confidence in the test results but require larger samples.

- The desired significance level. This indicates how likely we are to detect a difference between the control and the experiment when it doesn’t exist. Lower values give us more confidence in the test results but require larger samples.

Once we have established these parameters, we can plug them into one of many A/B test sample size calculators–Evan Miller’s is arguably the most popular, but any popular A/B testing platform (e.g., LaunchDarkly, Optimizely, VWO) will also do the math for you.

Finally, we must decide how long we want to run our test. It’s usually recommended to run tests for at least two complete business cycles. This helps to protect our experiment from a few common pitfalls, such as external validity threats, novelty/maturation effects, and change aversion. We’ll cover these in a separate article!

3. Launching the Experiment

The next step is to work with our product team to design and implement our experiment.

Most modern A/B testing platforms allow non-technical users to launch tests with complete autonomy. After copy-pasting a snippet of JavaScript code to their website, brand operators can design and launch experiments that alter UI elements without touching a single line of code: users can alter page layout, CTA styles, and other elements. This capability allows product managers and stakeholders to move quickly and saves engineering bandwidth for high-impact product work. However, it also comes with some caveats of which users are typically unaware.

First of all, experiments that have been implemented without the assistance of a product team might present bugs or inconsistencies that make them less palatable to new and existing brand customers. This might skew our test results: what if our latest category page experiment failed to outperform the control because the customer experience was counterintuitive? In some cases, such pitfalls can completely invalidate an experiment, resulting in a waste of resources.

Secondly, it’s not uncommon for a large brand to run tens of experiments simultaneously. When experiments run in the browser, they can have significant performance implications and harm the user experience.

Brands should invest in A/B testing infrastructure that allows them to design and launch experiments quickly while continuing to involve the product team. This often comes in the form of streamlined processes, strong design/development primitives–such as a reusable design system and UI kit–and clear guidelines on what is considered “good enough” for an experiment.

4. Analyzing Test Results

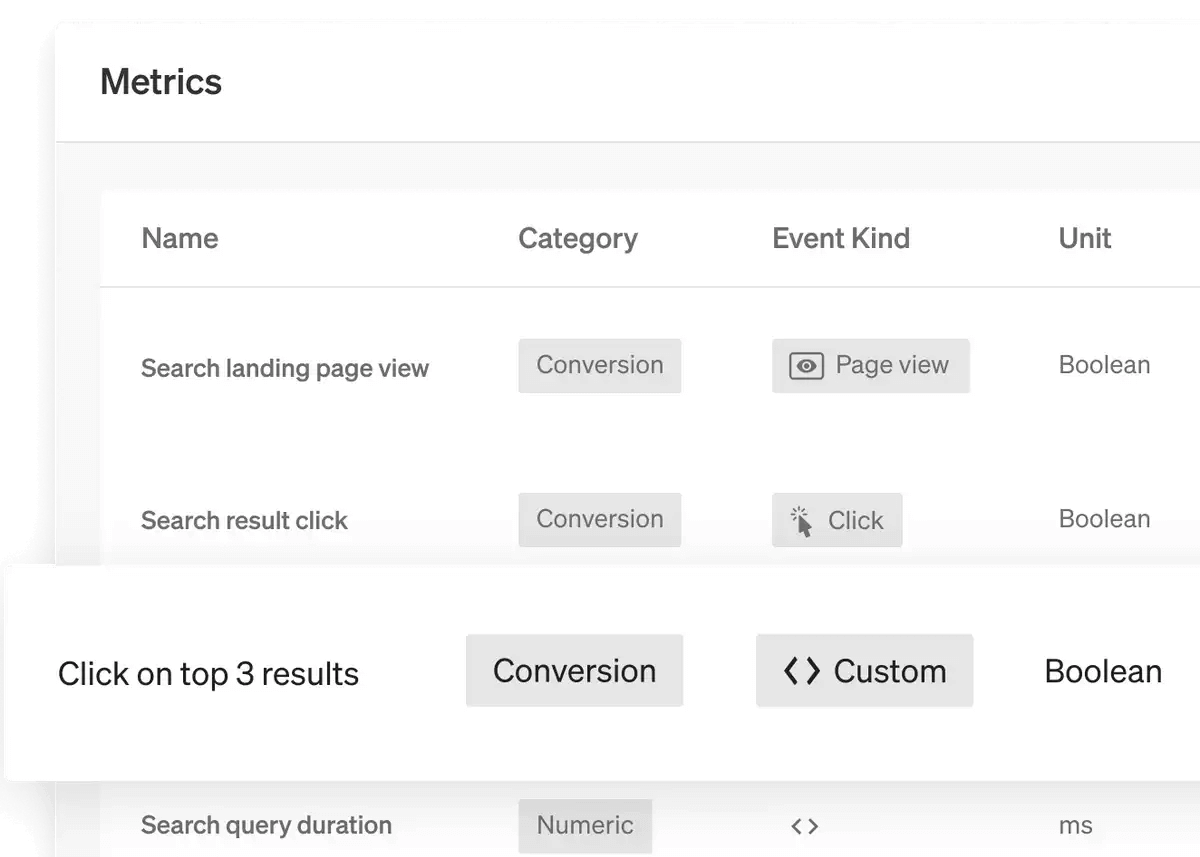

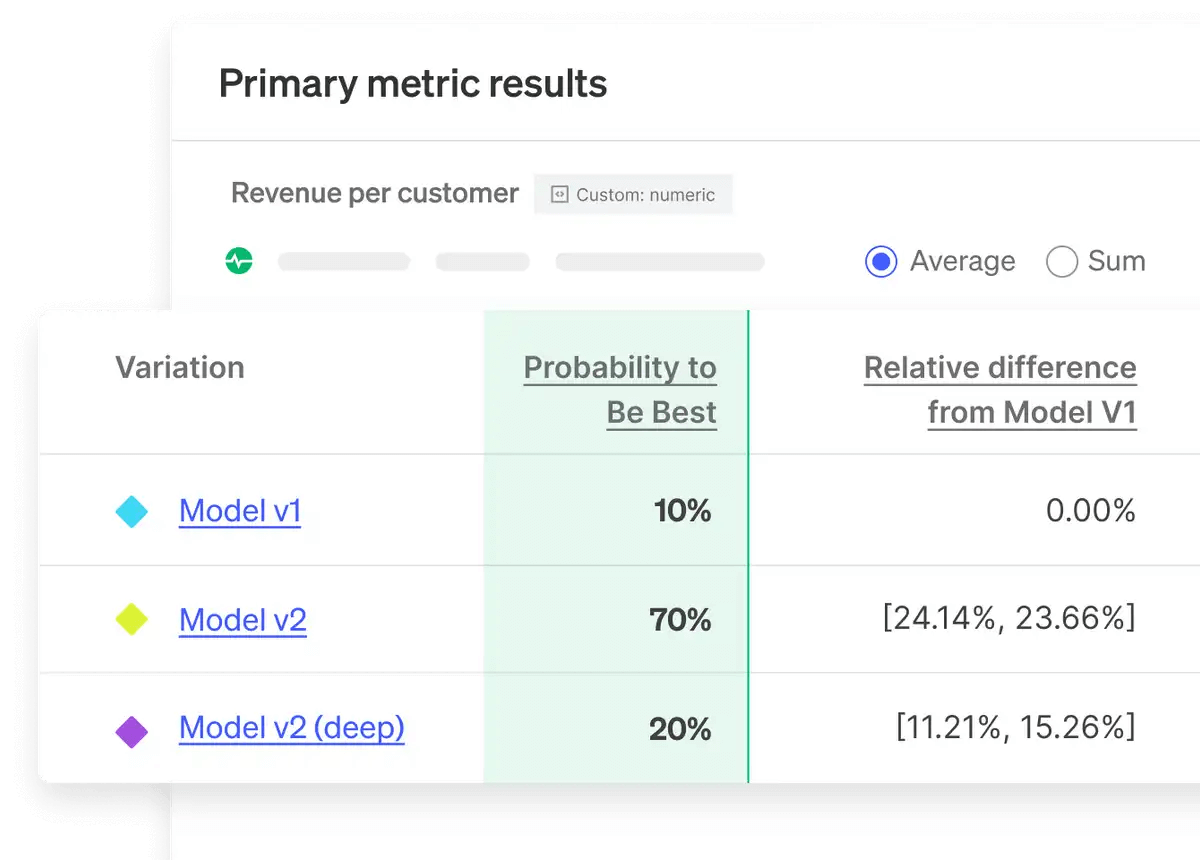

Once the test is completed, it’s time to analyze the results. Typically, there are two questions we’re looking to answer for each A/B test.

The first and most obvious is whether the experiment outperformed the control–or, in other words, whether our hypothesis was confirmed or disproven by the test. If the experiment outperforms the control, we can say that our hypothesis is correct–within the established levels of statistical confidence, of course. We might also find that the control outperformed the experiment or that the test was inconclusive (i.e., neither variation significantly outperformed the other, and no winner can be established).

The second question is what secondary implications the test had on our experiment population. This might involve looking at other metrics or specific customer segments to understand whether the test affected our customers in non-immediate ways. Here are a couple of examples:

-

A test might tell us that offering 50% off on the first order of our subscription product increases our subscription activation rate. However, when we look at secondary metrics, we might find that the experiment group also has a much lower retention rate than the control group, causing us to lose money on every conversion. Is this outcome desirable for our eCommerce business?

-

A test might be inconclusive or present the control group as a global winner. However, when we dive into the data, we might find that the experiment blatantly outperformed the control for specific segments. Sometimes, this might indicate an opportunity to offer a more personalized experience.

As a rule of thumb, it can be helpful to map some of these secondary considerations when designing the test. However, this analysis is very exploratory, and it’s impossible to list all the possible outcomes in advance. Brands should take the time to review test results with different stakeholders so that everyone can bring their KPIs and perspective to the table.

Once we have finished analyzing the results, it’s time to archive them. This is a step that most practitioners skip, but it’s incredibly valuable: archiving the results of our A/B tests allows us to establish them as a first-class research methodology rather than a short-term approach to conversion optimization. Ideally, insights derived from A/B tests should systematically become part of our organizational knowledge.

5. (Bonus) Re-Testing as Needed

What’s true today might not be true tomorrow. When they first embrace a product-led approach to brand growth, we see many founders make the mistake of thinking that any insights they have uncovered are set in stone and will never need to be revisited. In reality, markets change constantly, and so does our business.

We don’t encourage re-running A/B tests for the simple sake of it–in most situations, the effort of re-testing far outweighs the benefits. However, practitioners should feel comfortable re-running an old test or testing old assumptions in novel ways.

An End-to-End A/B Test Example

Let’s see what an end-to-end A/B test execution might look like by following the process we have just outlined:

-

As we’ve mentioned, it all starts with identifying a problem space we want to explore. In this case, let’s assume we are trying to understand why our product page has a particularly high bounce rate. We draft a Product Opportunity Assessment, collecting all the information we have gathered.

-

We collect a few hypotheses about why this might be happening, based on what we know about the business and our customers: maybe visitors can’t find critical information in the product description; maybe the particular variant they are looking for is out of stock; or maybe they aren’t willing to pay shipping costs.

-

We start by testing the shipping cost hypothesis. After looking at Google Analytics, we conclude that increasing add-to-cart rates by an absolute 10% would be considered a win.

-

Because offering free shipping comes at a considerable cost, we want to be very confident about our test results, so we pick a 95% statistical power and a 10% significance level for our test.

-

We plug the numbers into our favorite A/B test sample size calculator, which tells us we’ll need to direct 858 visitors to each branch of our test. Based on our traffic patterns, we think we can accomplish this in two weeks.

-

We work with our design and engineering team to implement an experiment that offers customers free shipping and displays the offer prominently on the product page.

-

We use our favorite A/B testing tool to launch the test.

-

After two weeks, we look at the results of the test. It turns out that the test was overall inconclusive: offering free shipping did not significantly affect the add-to-cart rate. However, when we look into the results across different segments, we find that the experiment group outperformed the control group for products over $150.

-

We archive the results of the test and refine our POA accordingly.

Now that we have the results of the test, we may decide to:

-

Offer free shipping to everyone. Our business might have a policy of offering the same shipping conditions to everyone.

-

Offer free shipping only on products over $150 to maximize our ROI. We might even play with different placements of the free shipping indication: what if we included the banner in the shopping cart or checkout page?

-

Run another A/B test on a more promising target audience. We could test free shipping for products over $150, to be confident that it will actually move the needle for that segment.

-

Collect more information through alternative product research methodologies like user testing or heatmaps.

-

Not do anything: a more detailed evaluation might find that free shipping is not the highest-impact solution to this problem (e.g., perhaps we’d be better off adding testimonials to the product page or offering an upsell).

As we’ve mentioned, an A/B test doesn’t have to lead to immediate action. By treating our tests as a source of insights rather than a mere CRO methodology, we can deepen our knowledge of our customers with statistically verifiable, data-driven information that will enrich our product strategy and ultimately increase our bottom line.

What Comes Next

We could talk for ages about the pros, cons, prerequisites, and implications of A/B testing, but this is more than enough for a single article.

In the following articles, we’ll explore the most common pitfalls operators, marketers, and product managers incur when setting up and executing an A/B testing strategy. We’ll talk about statistical significance, the shortcomings of using A/B testing as your only source of product knowledge, and what alternative strategies brands must employ before considering running an A/B testing operation.

In the meantime, if you have any questions about any topics we have discussed or need help designing an A/B testing strategy for your eCommerce site, don’t hesitate to reach out!